DCPZ In Action , Vol. V:

Anne Leflot & Gerald D. Smith, Jr.

“DCPZ In Action” is our feature that highlights the many ways in which DCPZ educators are using Project Zero ideas in their practice. We hope that our readers will be inspired to try something new in their own setting. Each of these articles will also be posted in a DCPZ Newsletter as well as published blog posts on our Professional Development Collaborative website.

Cross-Cultural Exchanges: Bridging Divides Across a City and an Ocean

Anne Leflot is a French literature teacher at Washington International School in Northwest DC.

Anne Leflot is a French literature teacher at Washington International School in Northwest DC.

Gerald D. Smith, Jr. is Principal of St. Thomas More Catholic Academy in Southeast DC.

Gerald D. Smith, Jr. is Principal of St. Thomas More Catholic Academy in Southeast DC.

Both Anne and Gerald are founding, “origin” educators in the JusticexDesign (JxD) initiative. JxD, an outgrowth of the Making Across the Curriculum project, was launched by Project Zero researcher Sarah Sheya in 2019-20 with a cohort of ten educators from six diverse schools in Washington, DC. JxD investigates educational strategies that encourage young people to engage critically with the design of their world.

This year, Gerald and Anne collaborated on a project that not only brought together their grade 8 and grade 9 students, respectively, in DC, but also brought those students together with peers at a school in Paris, France, in order to compare and analyze their neighborhoods through a systems and social justice lens. Their responses to our questions, below, have been edited slightly for clarity and brevity.

How did the project come together?

Washington International School (WIS) organizes a school exchange every year for grade 8 students with a school in Paris. Due to the pandemic, this exchange could not take place in 2020. From there was born the idea to organize a virtual exchange for the rising grade 9 students, with a specific focus on the intercultural exploration of the systems that structure our daily lives. Anne had had the idea for a virtual exchange ten years ago when she discovered the work of Sabine Levet, a Senior Lecturer in French in the Global Studies and Languages section at MIT and one of the original developers and current Project Director of Cultura, a semi-virtual exchange program that creates a bridge between various communities globally. In this work, there were opportunities to create spaces for conversations that bring to light the differences that exist across our global community.

The goals of the project:

- For WIS Students:

- To develop their ability to converse and reflect in French and develop their ability to translate from French to English and from English to French (WIS students were the only bilingual students in this exchange).

- For Collège Gambetta and STM Students:

- To be exposed to a foreign language;

- To learn how to navigate an environment that is new and challenging;

- To take risks; and

- To collaborate despite language barriers.

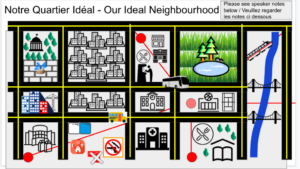

- For all of the students:

- To understand the complexity of the systems that govern their life, as well as their role within it;

- To discover and compare their own culture’s systems within a large, racially divided city;

- To conduct an in-depth reflection on the concepts of power, privilege, representation, and access on an international scale; and

- To learn about civic engagement.

How did the project evolve over time? What challenges did you encounter?

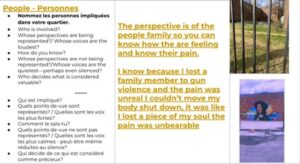

What are some of the outcomes you’ve noticed from the project?

We noticed a high level of engagement and motivation. Students from each school would frequently ask us when we would all meet again. Being able to collaborate with students from other schools and share some components of their personal lives was a big takeaway for them and a little bit of fresh air during this pandemic.