Identity

Emily Veres

Washington International School

IB Diploma Program Biology

Grade 11

Overview

In this unit, Biology teacher Emily Veres was hoping to find a way to address the complexities of identity--specifically, identity as a sociocultural construct within the confines of a content-heavy International Baccalaureate Diploma Program Biology course. She partnered with National Portrait Gallery educator Briana White to use a museum visit as the cornerstone to this exploration.

Learning Goals

How is identity constructed? How do we connect polygenic inheritance to identity? How is race connected to identity?

UNIT/LESSON PLANS:

(in collaboration with Briana Zavadil White at the National Portrait Gallery)

Context

Washington International School (WIS) is a coeducational independent school offering 900+ students a challenging international curriculum and rich language program from PreK-12th grade. Over 60% of its students graduate with a prestigious International Baccalaureate (IB) bilingual diploma. Located in Washington, D.C., WIS has a lengthy history of encouraging global responsibility and social inclusiveness.

As this two-year course requires students to learn and apply an enormous quantity of material, it is a particular challenge for teachers desiring to slow down the learning and engage with global issues. In starting to explore ways to address this concept of identity, I read several articles and watched many TEDTalks. One of the articles I read is titled “Can You Tell Your Ethnic Identity From Your DNA?,” and it briefly discusses how and why it’s not entirely possible for scientists to determine much about ethnicity or personal origin from a DNA sample, despite what certain companies claim. There were also a few TEDTalks (linked below) that provided some ideas and talking points about how I might move beyond the curriculum.

TEDTalks:

- Nina Jablonski: Skin color is an illusion

Nina Jablonski says that differing skin colors are simply our bodies’ adaptation to varied climates and levels of UV exposure. Charles Darwin disagreed with this theory, but she explains that’s because he did not have access to NASA.

- Angélica Dass: The beauty of human skin in every color

Angélica Dass’s photography challenges how we think about skin color and ethnic identity. In this personal talk, hear about the inspiration behind her portrait project, Humanæ, and her pursuit to document humanity’s true colors rather than the untrue white, red, black and yellow associated with race.

The following set of activities was carried out at the conclusion of our unit on genes and inheritance. As part of the IB Biology curriculum we look at genes, chromosomes, epigenetics and various aspects of determination of biological sex (chromosomes, hormones, etc). I thought it would be a perfect time to dive more deeply into the concept of identity, what it means, and how we might construct it. I was curious as to what students felt makes up their identity and whether they would describe their inward-facing and outward-facing identities using the same descriptors. By asking the overarching question, How is identity constructed?, I hoped to connect identity to genetics since it is a syllabus topic. Specifically, I used polygenic inheritance as a starting point for the conversation as human skin color is controlled by more than two genes. A second goal was to move beyond Biology and consider the implications of identity on a larger scale by including race as a construct, leading us to consider identity from a more global perspective.

I try to seek out opportunities to extend beyond the IB Biology syllabus in relevant and authentic ways. I believe that it gives students the opportunity to slow down and consider the implications of Biology beyond their textbook by allowing for rich conversations to occur based around open-ended questions. The concept of identity is one that could be discussed at a local or global level and can raise a variety of complex issues, such as race as a human construct, culture and ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, language, etc. Each of these could be addressed individually or many could be linked together more broadly to determine the overall impact on the identity of a person or a group of persons.

Key Learning Experiences

Step 1: Introduction to Topic

HOMEWORK (assigned the day before our in-class Chalk Talk)

Students had already learned about polygenic inheritance and certain inherited characteristics that are controlled by more than two genes, skin color being one of them. I asked them to watch the Dass TEDTalk (linked above) and answer the questions below in their process journals.

Question to answer before watching TEDTalk:

- Re-read the section on polygenic inheritance from the IB Biology Course Companion textbook (Oxford University Press, 2017; pgs 449-451). If all people (except for albinos) have the same number of melanocytes (cells capable of producing melanin), why then do people have differing quantities of melanin present?

Questions to answer after watching TEDTalk:

- What are your initial thoughts after watching this talk?

- What percentage difference of DNA would you predict exists between two individuals (regardless of melanin)?

- How might this talk help us to discuss identity?

Step 2: Pre-Museum Visit Lesson

Discuss TEDTalk: share out individual student answers from TEDTalk assignment as a group, document on whiteboard.

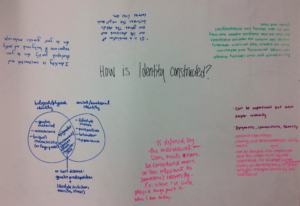

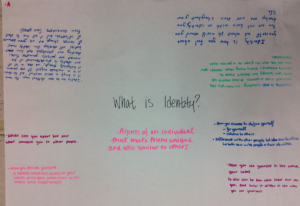

Chalk Talk (reflect in process journals first, then class chalk talk):

- What is identity?

- How is identity constructed?

- Within the 0.01-0.03% variations in human DNA, what is it that makes us individuals?

Students answered each question on poster paper and then we did a class gallery walk, pausing at each poster to comment on each others’ thoughts and adding new ideas as they arose.

HOMEWORK (to be completed before the museum visit):

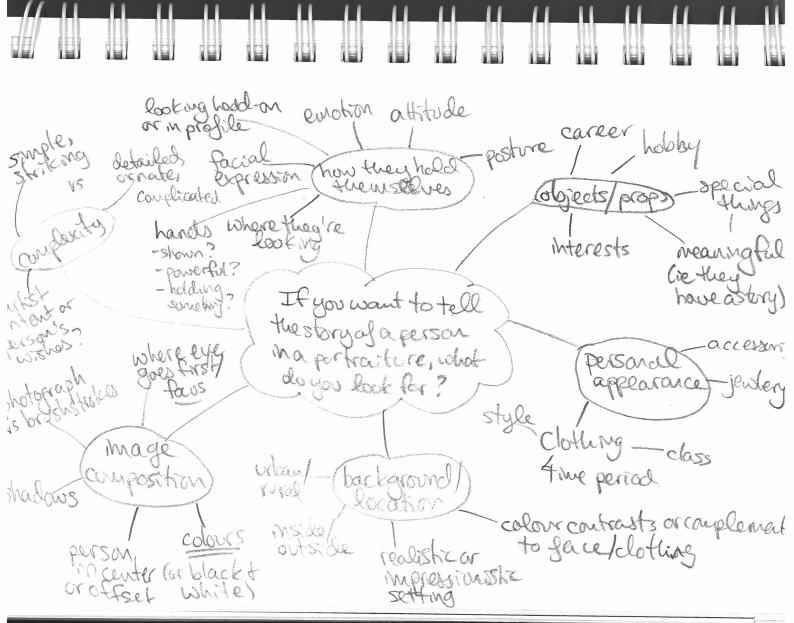

1. What evidence of a person’s life story would you expect to find in a portrait?

2. Sketch/create or find a portrait that represents how an individual’s story is told via visual clues in the portrait.

Step 3: Visit to National Portrait Gallery

We started out the visit with an introduction to the National Portrait Gallery mission and description of its collection. Each student was asked to answer the questions, What is a portrait and how do you define it?, in their process journals. We planned to visit three works of art in the same gallery space as well as give the students some time to choose their own work to explore portraiture and identity.

Cupcake Katy by Will Cotton (link to image can be found here)

We decided to start with this painting to introduce portraiture as well as to examine how portraits can conceal or reveal. We wanted the students to start with an individual who was familiar but offered the opportunity for the group to get a feel for what aspects of identity are concealed/revealed. We asked the students to think back to their definition of a portrait and share out to the group their thoughts about this portrait.

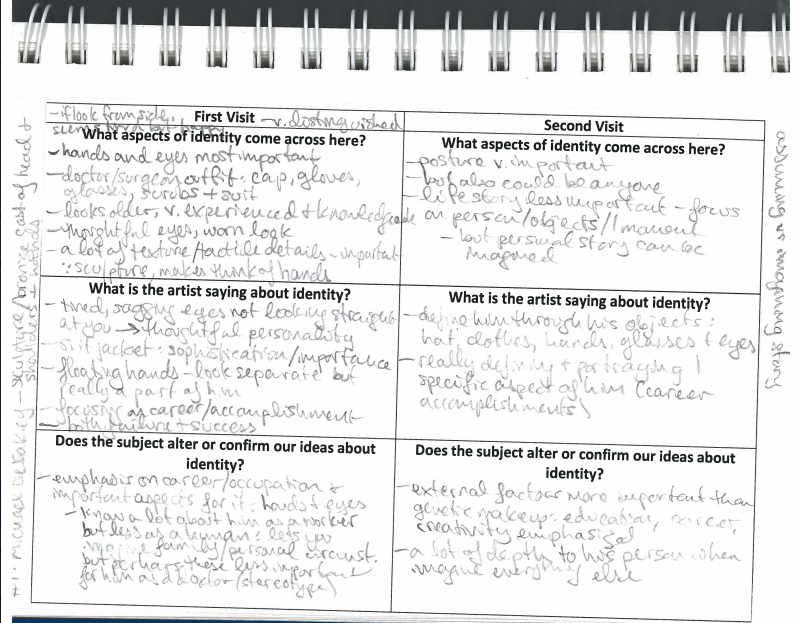

Individual exploration of portraiture in the exhibit Twentieth Century Americans: 1950-1990

Students visited the gallery across the hall and were asked to choose a portrait to explore. They answered the questions listed below in their process journals. Since we were going to come back to this portrait at the end of the gallery experience we didn’t do any debriefing until then.

- What aspects of identity come across here?

- What is the artist saying about identity?

- Does the subject alter our own ideas about identity?

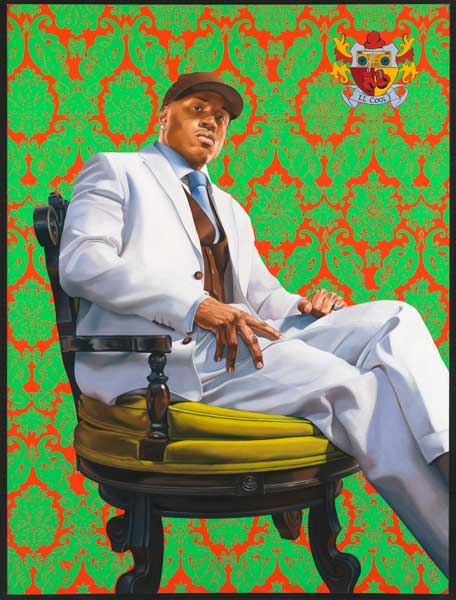

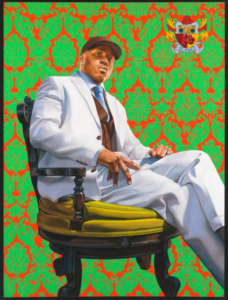

LL Cool J by Kehinde Wiley (link to image can be found here)

This portrait was chosen because the background is completely the opposite of Katy Perry and it shares the appropriation of an image in common with Shimomura (below). This image was an excellent starting ground should the conversation of race as a construct arise. It’s also an opportunity to discuss:

- purpose and decision-making in portraiture

- the link back to the Chalk Talk about percent differences in DNA and what makes us individuals

- the link back to polygenic inheritance

Approach:

- Observation for one minute and then discuss in pairs any initial observations or questions. These observations and questions were then shared out to the larger group.

- Compare and contrast with John D. Rockefeller by John Singer Sargent. (The portrait of LL Cool J was based on John Singer Sargent’s painting of JDR, yet there are significant differences that students can use to draw conclusions about what the artist or sitter is conveying about identity.) This was also done in pairs and shared out to larger group.

- How does this portrait link back to our three Chalk Talk questions? This was also done in pairs and shared out to larger group.

Portrayal of African Americans; skin color and genetics; race as a construct; etc

Shimomura Crossing the Delaware by Roger Shimomura (link to image can be found here)

This was chosen as an entry point to discuss the role culture and experience can play with identity. We decided that, although the Unveiling Stories routine was an amazing way to discover more about this piece, because we had so many other works of art, we would start the conversation by comparing and contrasting between Shimomura’s painting and the original painting it’s based on, Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze.

Approach:

- Compare and contrast with the two works of art (individual notes first in sketchbook).

- Group compare and contrast discussion and then sharing of individual thoughts to the larger group.

In pairs, use the Claim-Support-Question Thinking Routine to create two claims, two supports and two questions about this artwork, and write them down in sketchbooks. - How does this portrait link back to our three Chalk Talk questions?

(Could be an opportunity to discuss the tension between biological features and cultural identity–a powerful exploration of individuals whose biological features provide evidence for a particular culture but who grew up outside of the culture–Chinese/Japanese-Americans; Afro-Europeans; etc.)

Individual exploration of portraiture in Twentieth Century Americans: 1950-1990

Students revisit portraits chosen during the individual exploration and answered the same questions again.

- What aspects of identity come across here?

- What is the artist saying about identity?

- Does the subject alter our own ideas about identity?

How has your experience in the gallery altered your answers? Confirmed your answers? Share out using the I Used to Think…But Now I Think Thinking Routine.

Step 4: Culminating Learning Experience–Post-Museum Visit

Revisit Chalk Talk and reflect using the 3Y’s Global Thinking Routine:

- Why does using art to discuss identity matter to me? my community? the world?

- What can you cite as evidence in answering these questions?

- Are there other forms of art besides portraiture that may link to any of these?

Reflection: How has this experience shaped your ideas about identity?

At the last minute I found another appropriation of Washington Crossing the Delaware painted by Robert Colescott called George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware. I didn’t have anything specific planned but wanted to show them the image, so I printed it out and briefly described the intent of the artist and addressed any questions.

Teacher Reflections

This year I have a small group of IB Diploma Biology students, perfect for trying out this lesson. A challenge arose in that this particular group was quiet, and I was worried they wouldn’t be as actively answering questions and taking risks as previous classes I have taught. Because Briana and I had purposely chosen to use different strategies at each portrait so as not to repeat the same thing, students were given the opportunity to think either individually or in pairs before sharing out to the group as a whole for most of the portraits selected–something that worked better than just simply sharing out in a group situation.

I was surprised that the students seemed to struggle a bit with the Shimomura painting, and I’m still trying to consider why it was harder for them–whether we had already spent too much time in the gallery and they were tired, or whether they lacked the historical context to understand the work of art. We all found questions 1 and 2 from the Chalk Talk (what is identity and how is identity constructed?) a bit repetitive and it’s hard to answer one without bringing in answers from the other. So I would lump these two questions together on the first poster and use ‘What internal and external factors make up our identity?’ as the second question. I would keep the third Chalk Talk question the same (about the percentage differences in DNA).

We tried to do an enormous amount of exploration in three short classes and for the most part we were successful, but this also means that it’s likely we spent too much time on some things and not enough on others. The students felt overall that this should have been a shorter unit, given the major constraints of the Biology curriculum. I feel a similar concern, but I think that if we had made sure to really link each portrait back to the idea of genetics and identity it would have been a stronger lesson and one worth the time away from the content.

In approaching a plan for next year I won’t spend as much time reviewing the Chalk Talks in the post-museum visit and make sure to immediately link identity with genetics before the 3Y’s. I would also like to dive more deeply into the tension between biological and cultural identity as I mentioned with Shimomura (when individuals have biological traits that their culture does not necessarily support). I had wanted to get there, but the students didn’t quite make those connections and so next time I would like to be prepared with specific questions. Another possibility is to use the Unveiling Stories Global Thinking Routine with Shimomura and spend the entire time on that work of art instead of trying to see three pieces altogether. It is also possible that we could move beyond genetics and take a more sociological/psychological angle with the questions we ask, such as, ‘How is identity constructed and by whom?’ Briana and I also tinkered with the idea that instead of the students searching for a portrait (as homework before the museum visit) that represents how an individual’s story is told via visual clues in the portrait, they could do a rough contour sketch of themselves, and, in the void of the image, write what makes up their identity.

Any teacher of students in an advanced class such as IB or AP is going to be nervous about taking class time to visit a museum when it isn’t directly related to the content/syllabus. I was certainly nervous about how my students might respond when I told them we were going to take a trip to the museum as well as use class time to discuss identity. I was very happy with their anonymous feedback and will take their suggestions for making sure that we link back to Biology in addition to exploring identity in a more global context. The students commented that they felt more open for debate at the museum, that they could step away from memorizing and textbooks and explore more thoughtfully in the space provided by the museum. One said that visiting the museum “helped [her] see more input and ideas from my peers” as she was able to comprehend the nuances within the artwork directly in front of her. I would imagine there is even more flexibility if this or a similar unit were to be used with ninth or tenth graders, simply because there is more curricular flexibility.

The students were also able to identify connections between our unit on genetics and identity with other IB Diploma courses they are taking. For example, they commented on how it fit nicely with Theory of Knowledge in studying indigenous knowledge, in English where they are reading “Farewell, My Concubine,”, in French where they are exploring the comic book character Tintin, as well as links to activities carried out in other courses.

It was very helpful for my students to have access to a process journal (thanks, Briana!) in which to record their thoughts. It is also a way for them to keep the documentation of our global connections outside of their notes so it doesn’t get lost in the shuffle. I would really recommend using one as we cover a lot of ground, and it would be easy for early interactions or thoughts to get mixed up, which would make reflecting back on what you used to think versus now quite challenging.

Taking students out of their other classes can add a layer of complexity, but I fully believe it was worth it to bring the students to the gallery as several of the works we spent time exploring would not have been the same if I had projected the images or had brought in a poster. The students were able to get up close or view the works of art from different perspectives–which is not possible online. The brushstrokes, texture and size are also aspects that do not come across with an online or poster version. The portrait of LL Cool J would not be the same if we were going to view it online as the conversation we had comparing/contrasting with the portrait of John D. Rockefeller almost demands that the students experience the work in person.

Briana and I communicated via email, and we met a couple times at the Gallery to discuss the selection of artwork and the questions and goals we wanted to address with each work of art. She was absolutely key in helping me select which works of art to use as well as providing important contextual information that could help me make better connections within my teaching and classroom. Since many pieces could be used within the same space it made sense to take the students to the gallery and provide the experience of being able to move around the work of art as well as move closer. The mission of the National Portrait Gallery is to tell the story of America by portraying the people who shape the nation’s history, development and culture. This overlapped with an exploration of the wide scope of identity. Her guidance was invaluable, and I was additionally supported by the community of museum educators who chimed in with excellent questions and helpful suggestions. While I feel that I am able to touch upon several topics in my course that are in the realm of helping our students develop global competence, it would have been more challenging to make the connections with art if I had been working alone. Having access to information and knowledgeable museum educators made the experience incredibly rich for both me and my students.

Researcher Reflections

As a high school Biology teacher, Emily had the greatest challenge in finding a fit for exploring the arts and museum collections in her subject area during this project. Still, she plunged in with excitement and took a number of creative approaches in her planning. She has experimented for several years with Thinking Routines and with interdisciplinary approaches to her subject. Early in the year, she diverged from the IB Diploma Biology syllabus as students were learning about infectious diseases and virology in order to take a deep dive into the Zika virus. The students explored Zika from a variety of lenses, such as culture, politics, religion and public health. They then came together as a large group and created a large concept map that made connections among the different lenses, clearly showing their understanding of such a complex issue.

The project’s aim to pair a museum educator with a classroom teacher afforded Emily the opportunity to work with Briana White from the National Portrait Gallery on the Identity lessons. Emily articulates in her reflections the added value Briana’s involvement brought to the project. We have found without fail that the collaboration benefits both sides in unexpected ways. The classroom teacher has access to a knowledgeable source about the museum collections, whereas the museum educator has an opportunity to see how ideas developed for an in-gallery experience can resonate within an ongoing course of study. Usually museum educators deal with a one-time audience in the museum setting and rarely see the effect a workshop or talk has.

Emily’s candid reflection offers several insights for teachers who desire to bring the global into their classroom and move beyond the narrow content area so that students might make connections to broader issues. At the start, she has to be on the lookout for such opportunity. When the opportunity arises, the teacher needs to evaluate what the larger goals are beyond those focused on the content at hand. Furthermore, she must know her students and syllabus well enough to understand that the exploration is worth the time and energy expended. Finally, working in an environment with supportive and knowledgeable colleagues can embolden and inspire the teacher.

We had seen Emily take smaller forays into this territory in prior years. That experimentation made her a perfect candidate for this project.